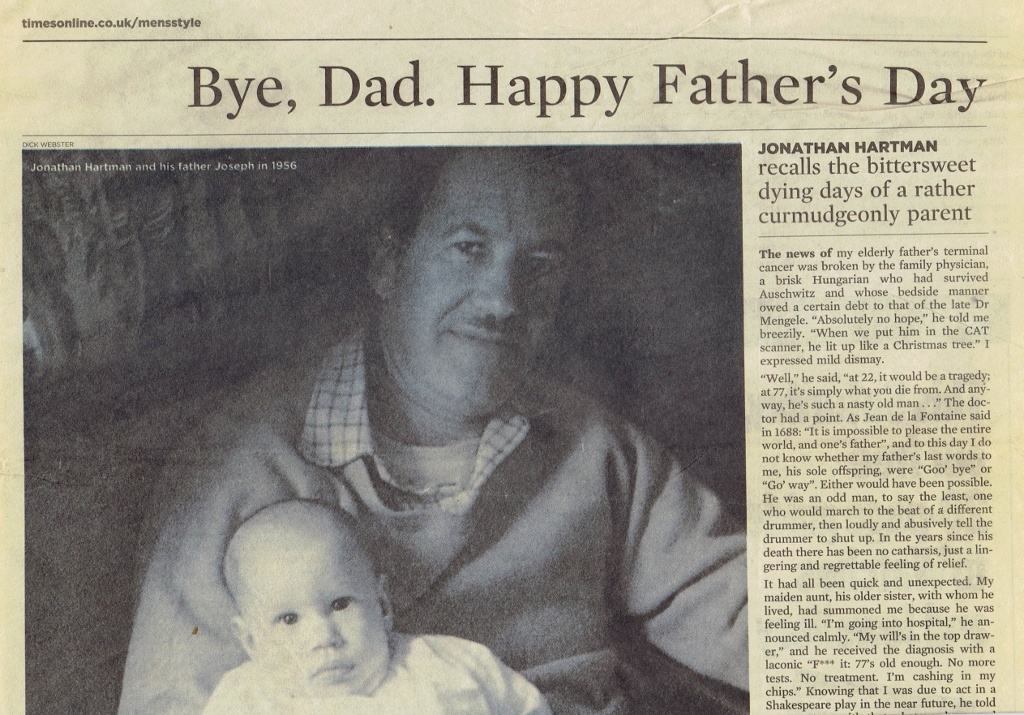

The news of my elderly father’s terminal cancer was broken by the family physician, a brisk Hungarian who’d survived Auschwitz and whose bedside manner owed a certain debt to that of the late Doktor Mengele. ‘Absolutely no hope’, he told me breezily,’ When we put him in the CAT scanner, he lit up like a Christmas tree’.

I expressed mild dismay.

‘Well’, he commiserated,’ at 22, it would be a tragedy. At 77, it’s simply what you die from. And anyway, he’s such a nasty old man…’

The doctor had a point. As Jean de la Fontaine said in 1688, ‘It is impossible to please the entire world, and one’s father’, and to this day I do not know whether my father’s last words to me, his sole offspring, were “Goo’ bye” or “Go’ way”. Either would have been possible. He was an odd man, to say the least, one who would march to the beat of a different drummer, and then loudly and abusively tell the drummer to shut up. In the years since his death, there has been no catharsis, just a lingering and regrettable feeling of relief.

It had all been quick and unexpected. My elderly maiden aunt, his older sister, with whom he lived, had summoned me because he was feeling ill. ‘I’m going into hospital’, he announced calmly. ‘My will’s in the top drawer’, and he received the diagnosis with a laconic ‘Fuck it. 77’s old enough. No more tests. No treatment. I’m cashing in my chips.’

Knowing I was contracted to act in a Shakespeare play in the near future, he told me to get on with that whatever happened to him. I smiled and with the gallows humour we shared told him that it would be more convenient if he’d either die before I started rehearsals, or hold off until the run ended. He chuckled grimly and said he’d work on it.

A difficult patient, he fearlessly faced eternity by ensuring he did not expire with any venom left unused, and took great delight in inflicting his personality on the other unfortunate denizens of his ward like a latter day suburban Caligula engineering a sanguine hit-and run.

‘Is that your father?’ the woman visiting the adjacent patient asked me-and without waiting for an answer demanded in astonished exasperation, ‘what kind of woman would marry a man like that?!’

My mere presence indicated that the unbelievable had indeed transpired, but I honestly couldn’t think of a rejoinder. I was too busy recalling The Unpleasantness of the Lemon Pie. Certain memories tend to brand themselves onto the frontal lobes, and a strange horror still overcomes me when I look at a lemon meringue.

That Mother had a martyrdom complex to rival Joan of Arc’s was indisputable. And the carpet did need cleaning. But to rent a steam cleaner, to transport it home, to move all the furniture herself while loudly refusing any offers of aid, to attempt the resurrection of a carpet which should have been retired years previously, and above all, afterwards, at the dinner table, to inform my father and eight year old self repeatedly and with great passion that should so much as the smallest crumb mar her efforts…

Father had had enough. With a dignity and deliberation that bordered on the ceremonial, he lifted an entire pie plate of lemon meringue over the carpet, and inverted it. Expressionless in the sepulchral hush that followed, he stepped into the detritus, whooped, and executed a few steps in an inspired imitation of James Brown- in retrospect, a superb tribute even considering his dual handicap of late middle age and Caucasianhood.

Mother’s reaction would have fascinated and inspired a legion of Berserkers. So traumatic was what followed that I honestly remember nothing of it- but this was yet another very typical chapter of a childhood spent trapped in a squash court, frantically attempting to dodge two ricocheting balls of antimatter.

My two pet turtles were a small grain of consolation, a rare gift from my father who solemnly informed me their names were Leopold and Loeb. It was years before I finally figured that one out.

As the old saying goes, ‘When a father helps a son, both laugh, and when a son helps a father, both cry’. But it wasn’t like that with us- day after day I sat by his bedside in hospital as his illness progressed, trying to keep him company, and whenever I tried to make conversation or express sympathy for his plight, he just snarled at me. I knew he was feeling slightly better once when he called me a prick and criticized my jacket. Finally I decided I’d had enough. And I resolved to confront him whether he was dying or not, to ask about all the rages, the insults, the unacknowledged birthdays, the broken promises and the vague feeling that my existence had always been something of an unwelcome surprise for him, born unexpectedly as I was in his mid-forties. Head held high, with the unshakeable determination of someone who’d made an irrevocable decision, I marched into his ward, approached his bed, fixed him with a steely glare…and he looked up at me and smiled.

I’d never before realized how blue his eyes were. ‘This is a nice hotel’, he said. ‘However did you find me? And where’s your room?’ He glanced from side to side, and then, with a soft, conspiratorial expression, confided, ‘I have to stay here until we find why I’m so lethargic. Does your mother know I’m sick?’

I conveyed her best wishes for his recovery, deeming this more discreet than reminding him she’d already been dead for eight years. There was a very pleasant old gentleman lying there, and it certainly wasn’t my father anymore. I knew then that there would never be any answers or revelations, and that all I could do now was sit, watch, and wait.

He began to sleep more and more, slipping away, and though he could not hear me I thanked him for the good times- for coping reasonably well with an energetic boy born to him in middle age, teaching me to ride my bicycle, to throw a ball, for making me a paper airplane once even though I’d woken him from a nap to do it, for instilling a love for Groucho Marx, and Shakespeare, for coaching me through a recitation of ‘The Shooting of Dan McGrew’, for teaching me to regard politicians and the sanctimoniously religious with suspicion, and ensuring that I knew iconoclasm is not necessarily a bad thing- breathes ever man with soul so dead/ who was not in the Thirties, Red?

However the problem with deathbeds is that they aren’t only depressing; they can be pretty boring as well. Sometimes you wish the dear (pre) deceased would just get on with it- but he rallied, once. A doctor dropped by to check his mental condition, and the old man, pathetically eager to please, made him welcome. ‘Do you know what day it is?’ the doctor asked. Father looked troubled, confused. ‘Well, do you know what month, what year? Who is the Prime Minister?’ It was if Father was trying desperately to hold onto handfuls of sand, and his puzzlement was both pathetic and palpable.

‘Does it bother you that you don’t know?’ asked the doctor gently.

And for one final time the old man gathered the remnants of his essence, and his eyes recovered their mockingly malignant glare. ‘No’, he said, firmly. ‘In fact, I don’t give a fuck’. Then he sighed, smiled at us pleasantly, and I knew the last of him had faded forever.

I knew very little about my father’s boyhood, never having had grandparents to tell me secrets. But one day as I sat next to him while he lay comatose in his oxygen tent, Sam, an aged relative, paid a visit. He told me how, as a child, he’d pulled his wagon on a five mile journey to visit my father, and had made him a toy car by pulling some boards off the back alley fence, and nailing them to it.

‘Then I left him to play with the thing, and had to walk all the way home because I didn’t have the wagon to push myself along in, or five cents for the tram. I was twelve, and he was seven.’ He regarded the dying man and smiled bleakly. ‘And you know, it’s been seventy years, and he hasn’t thanked me yet.’

Shortly thereafter the doctor told me he’d probably die in about two days, and I sat with him for most of that time, watching the breathing fade and restart, and watching the face sink in and yellow, which only served to accentuate the purplish circles growing around his eyes. Towards nightfall on the last day his respiration eased, the dreadful groaning he made as he tried to draw breath smoothing out a bit, and he opened his eyes. We looked at one another, and I told him gently that it had gone on long enough, that it was time, and to let himself slip away. I took his hand. As a child, his nightly farewell to me had always been, ‘Goodnight, sweet prince, and flights of angels sing thee to thy rest’.

‘Fear no more the heat of the sun’, I began ‘Nor the furious winter’s rages/ Thou thy worldly task has done/ Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages….

‘Go ’way’, he murmured. Or maybe it was goo’bye. I’ll never know. I kissed his forehead-it was burning with fever- and walked out. He died that night.

He left me his cynicism, his piercing stare, his love for cats, a deep baritone voice, and an enchantingly bitter sense of humour, which I’m flattered to be told I’ve inherited. Well, it’s something more enduring and certainly more valuable than the estate he bequeathed me. Father’s finances were severely depleted in his later years as a result of the refinements which old age confers on vice. And the vices of man are threefold- sex, intoxicants, and gambling, each man mixing colours from this particular palette and painting himself accordingly in varying hues and intensities.

Freed by divorce and retirement from the strictures of family life, my father was able to focus his undivided attention on horseracing. His enthusiasm for the Sport of Kings was only equaled by his ineptitude at betting. One could call him an extremely handicapped handicapper.

‘I hope I break even’, he’d say ruefully, ‘I need the money’. But the merest suspicion that my father had wagered money on it was enough to afflict the healthiest of horses with fractured cannon bones, equine encephalitis, or simply to cause the unfortunate beast to drop dead in its stall. There was rejoicing among the Jockey Club’s board of directors when the old man’s ravaged automobile (he referred to it as his ‘town car’, and the town was Pompeii) would wheeze its way into the parking lot at the racetrack. Red Rum’s feed bill was secure for another year.

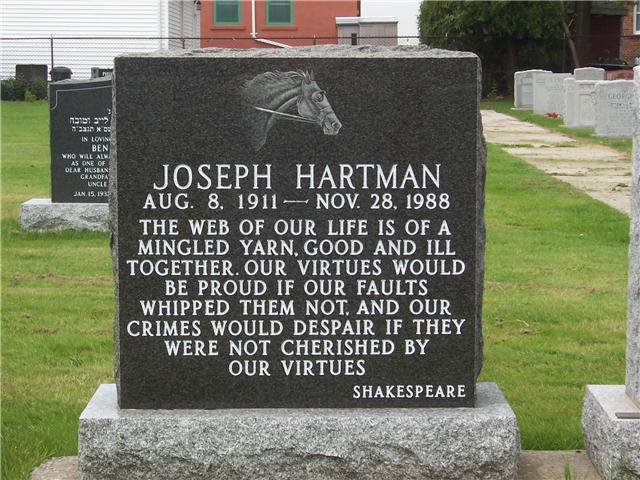

Inscriptions on tombstones bother me. ‘Sadly Missed’, ‘Dearly Beloved’, ‘Ever In Our Thoughts’-do only good people die? Is not a single one of the ‘bereaved’ ambivalent? I chose black granite for his stone, and a few lines from Shakespeare:

‘The web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together. Our virtues would be proud if our faults whipped them not, and our crimes would despair if they were not cherished by our virtues.’

And above his name and the dates is crosshatched the head of a hooded racehorse at full gallop, mane flying, and straining at the bit.

The stonecutter did a beautiful job. He even managed to capture the slightly desperate expression a horse wears when it’s running last.

Bye, Dad. Happy Father’s Day.

___________________________________

In the Kingdom of the Visually Challenged, the UniOcular Arts Council is King.

His Majesty King Jan of Bohemia never allowed mere trifles such as sanity to compromise his total blindness.

This redoubtable 14th Century warrior would often battle the Turks using his favourite weapon, the Military Flail, which consisted of a two foot iron-spiked oaken bar linked to a six-foot staff by three yards of heavy chain. Standing foursquare in his stirrups, shouting a Mitteleuropean warcry and whirling this Weapon of Messy Destruction around his head, he and horse were led towards the Ottoman hordes by a series of disposable Functionaries.

By all accounts, save for an extraordinary attrition rate of both horses and hapless Functionaries, Jan the Blind did surprisingly well at reducing legions of Turks to little heaps of steaming Baklava.

Of course, it took more than Johnny Turk to send this maniac West. It was we English who did for him at Crecy, in 1346, when, forsaking flail for broadsword, he attached his reins to those of the six knights flanking him, and charged our archers with predictable results. King and Knights were all found dead the next day, horses still tied together. And that, children, is how his three-feather coat of arms came to be appropriated, to this day borne by successive Princes of Wales.

Exactly how this worthy was convinced he could still fight while completely sightless is not recorded. It could have been by divine revelation, given the religious bent of his era. Or it could have been by someone from the medieval equivalent of the Arts Council, and I'm prepared to wager a considerable sum on the possibility- in fact, every penny of the £500 of your taxes that Arts Council England wasted hiring me to teach two blind actors how to stagefight.

The phone call came as I was yet again attempting to remember what being in work felt like. Primarily an actor, I possess a talent so rare that the casting directors, defeatists all, don't bother looking for it and my career path celebrates the triumph of fell circumstance over effort. Accordingly, I have sown another field of unemployment for myself, and can also be found not working as a fight choreographer.

Everyone's seen at least a minute or two's footage of a boxing match- a blurred flurry of action, and a man falls supine. Usually the knockout blow is too fast to follow, ergo the need for slow motion replay. Contrast this with John Wayne in a barroom brawl- wide roundhouse punches, exaggerated ducks, pauses where the combatants stagger about catching their breath- and that's all start-stop action, each repeated take and retake filmed from different distances and angles with plenty of time for the actors to rest in between and have their fake blood applied.

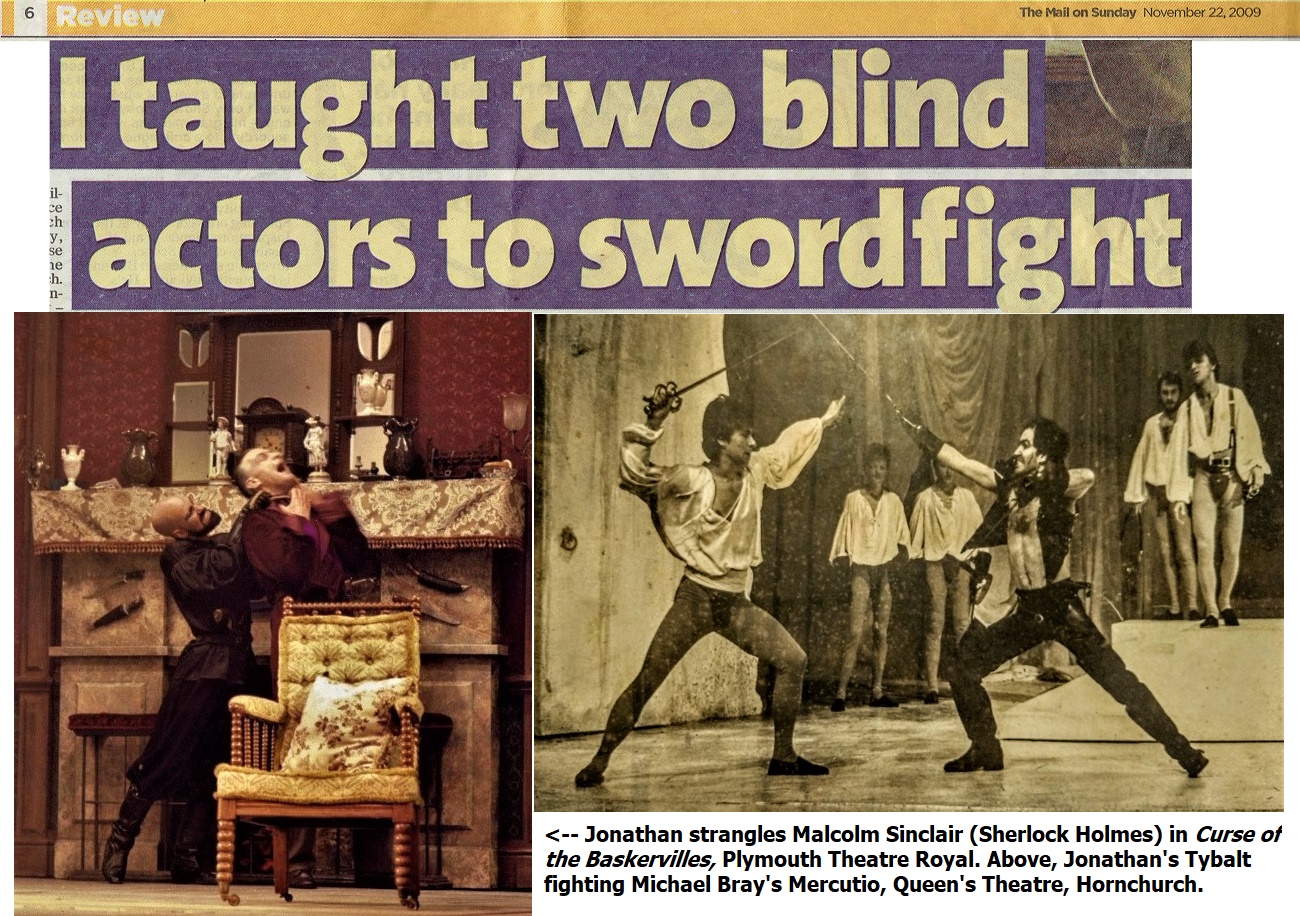

This luxury does not exist in live theatre. Once the lights go up, the play is on, and there's no stopping it. Thus, each stage fight must be a carefully choreographed, crisply executed piece of illusionary violence. Every action and reaction is worked out to the millisecond, the sequence and position of each swordcut, parry, punch, stride, collapse or roll set in stone and plotted to the inch. Rehearsals are intensive, exhausting, and as with any athletic endeavour, potentially dangerous. It is the Fight Director's job to create a logical, exciting, and, above all, safe combat where each move exemplifies the nature of each character- for instance, the dashing Robin Hood must fight in a different manner from the dastardly Sir Guy of Gisbourne- and above all he must never break the sacred contract with the audience.

That contract is a promise that the people who have come to be entertained must be concerned for the character but never for the actor. Let them enjoy worrying that the fiendish Tybalt is about to skewer poor Romeo, because the job is to give the audience a thrilling ride on the rollercoaster. But as soon as the patrons begin to worry about the possibility of a performer suffering real injury, the trust is broken, the illusion shattered, and no-one's having fun.

Thus, the ideal fight director combines the imagination and inventiveness of the Marquis de Sade with the nervous solicitude of a maiden great-aunt. Believe me; we only make it look easy.

So when Antonietta, an actress whose sanguinary demise I'd once staged (gunshot wound to the head, brains on the backdrop) rang to tell me she was teaching ˜Alexander Technique" to two mature acting students, and asked if I could spare the time from my impossibly crowded schedule to teach them a bit of stage combat, I was delighted. But she quoted a suspiciously high fee for the job, and I waited for the catch.

'They're both legally blind', she said casually.

At first I was positive that this was a windup, then afraid that it wasn't.

'There's a disability grant involved', I sighed.

'Yes. That's where the money for teaching is these days'

I hesitated for a moment; Ethics in the Blue Corner essayed a half-hearted jab at Wallet in the Red, then promptly took both a dive and the job.

***

'I want you to make sure we do this properly. It has to be good, not just good for Blindies', said Kay, a beautiful ash blonde with dilated jet pupils set in calm turquoise eyes.

'Blindies', I repeated dully.

'Absolutely', said Tom, unharnessing his dog so it could relax during the class. 'The ones in the chairs are called 'Wheelies'. Just treat us normally. Don't be embarrassed to say 'see' when you mean 'understand', for example. You can even ask me if I've felt any good books lately'.

And so we began. I could fault neither their courage nor their dedication, and they flung themselves in wholeheartedly. Kay, who had peripheral vision only due to Retinitis Pigmentosa, would observe what I demonstrated by subtly inclining her head at various angles, while Tom, eyeless from birth, copied my movements by swiftly running his hands over my limbs. We did fireman's lifts and carries. We did slaps, finding the range by holding one another at arm's length. I taught them phoney hairpulls, faux knees to the groin, and fake elbow smashes to the solar plexus. We did strangulation, manual and by ligature. At their insistence, we even did a bit of swordplay and quarterstaff- very slowly of course- in order to give them both the idea of what it was like to hold weapons. We then set the comic domestic scuffle from Noel Coward's Private Lives, rehearsed it several times, then, at week's end, arranged a few chairs at one end of the studio for a viewing.

Several people connected with the Arts Council arrived to see the results of the exercise, a group comprising various permutations of sexuality, disability, ethnicity, and comfortable sandals. All were middle class. Some were Advisors to Arts Consultants, some were Consultants to Arts Advisors, and all were failed performers, each one a testimonial to the efficacy of the recruitment ads in the Creative and Media Section of the Guardian Newspaper. If Illusion is the theatre's stock in trade, Self- Delusion is the preserve of Arts Boards.

Afterwards we all went out to a nearby wine bar, and fulsome praise was heaped on everyone connected with the week's training.

But tread softly; for you tread on their dreams... as actors they were fine. As fighters, to put it charitably, they were less so, and it was not simply a question of limited rehearsal time. There was no flow, eye contact, which is the prime means of communication in stage violence, was naturally nonexistent, the moves were muddy, furniture bumped into, and though they got through it without injury, I was concerned for Tom and Kay, not amused by Amanda and Elyot. When one considers that the run of a play comprises eight performances a week, including matinees, the potential for mishap begins to multiply unnervingly.

Plays change nightly. Timing differs, conditions shift, and the strangest things can be commonplace. I once choreographed a Macbeth where the lead developed a very serious coke dependency, and MacDuff's method of screwing his courage to the sticking place to face the snuffling lunatic for the final duel was to get drunk during the intermission- but at least both actors could see. I've witnessed mercifully few accidents in my professional career; nevertheless when it happens the sickening feeling affecting both cast and audience is palpable.

I would never allow a situation to develop where an actor was endangering a fighting partner through lack of talent or under-rehearsal. The moves would be simplified, or in an extreme situation, the performer replaced. In an instance like this, though, one's hands are tied. I cannot blame the actors involved- like me, they simply want to work. And in taking the job in the first place, I concede that I did what our current political climate considers worthy rather than saying what any sane person would know to be honest. But a paying audience deserves professionalism, and under those circumstances I would not be able to provide it.

It seems that wherever grants are concerned, those who give the orders and dole out the money, as usual, have no idea of the realities involved, and resolutely see things as they should be and not as they are. But there are no rewards for effort in the real world, and I can only paraphrase General Bosquet as he sadly watched the Charge of the Light Brigade:

'C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas le théâtre'.

_________________________________________________________________________

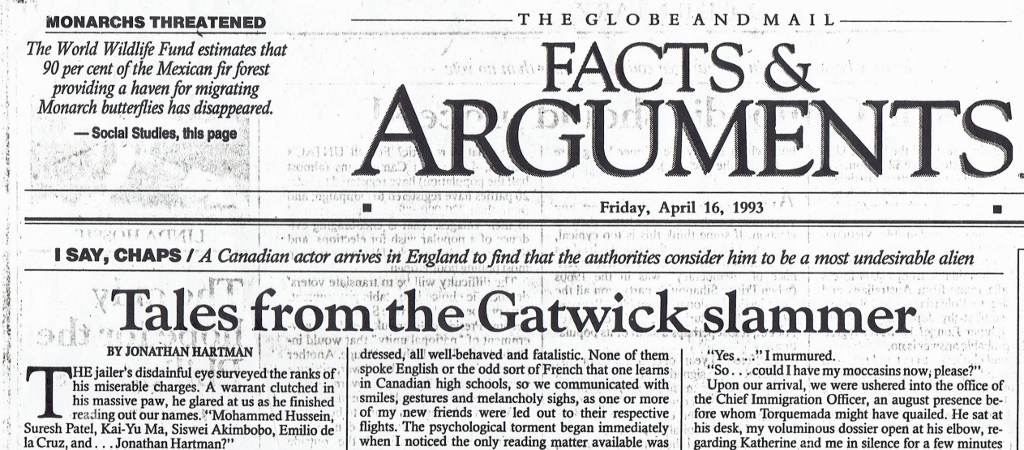

The gaoler's disdainful eye surveyed the ranks of his miserable charges with the contemptuous air of a mandarin examining prisoners during the Boxer Rebellion. A warrant clutched in his massive paw, he glared at us as he finished reading out our names. "... Mohammed Hussein, Suresh Patel, Ma Kai-Yu, Siswei Akimbobo, Emilio de la Cruz, and... Jonathan Hartman?"

"Aye, good turnkey," I declaimed in ringing Shakespearean tones.” Present and held in durance vile."

He looked at me, perplexed. "Wot the bloody 'ell are yew doin' in ‘ere?”

Yes, I'm now held in great regard by the Triads of Hong Kong. High- ranking members of the Colombian cocaine cartel call me friend. I'm blood brother to that nameless Mid-Eastern patriarch, he who is hesitantly referred to in hushed tones by his fanatical acolytes (vicious terrorists to a man) as "The 'Black Hand of God". And if I ever wind up on the Ivory Coast, I'll never lack for a mud hut in which to lay my head.

For an ordinary mortal, all this would represent the fruits of a lifetime spent wandering through the forbidden hinterlands of the planet. Yet I managed it easily with a holiday flight to England and a brief confinement in the Gatwick Airport Immigration Detention Centre.

Admittedly, it was my fault. I shouldn't have tried to return a mere eight months after my near-compulsory departure. I'm no stranger to Britain - lived there for years. As anyone unfortunate enough to be trapped next to me at a party could tell you, my repeated auditions for several Canadian drama schools were unsuccessful, but I did manage to obtain a place at the Bristol Old Vic school in England, where my contemporaries included Daniel Day-Lewis, Greta Scacchi, Miranda Richardson, Matt (Max Headroom) Frewer, Samantha (Miss Moneypenny) Bond and several other luminaries who wouldn't remember me either.

After a spectacularly unsuccessful return to Canada upon completion of my studies, I secured a temporary non-renewable work permit, went back to England, and worked. I acted in repertory theatres, did Shakespeare on national tours, and appeared twice in the West End, once for seven months with Charlton Heston. During the lean times, I taught medieval sword fighting in various drama schools.

But I had overstayed my visa by four years, and my letters to various MPs demanding the same rights of settlement we afford to our traditional allies, the French and the Germans, were apparently losing their power to amuse. The demands from the Home Office for my departure eventually became too strident to ignore, and to avoid deportation, I left of my own accord.

Spoiled by the more democratic ethos of the British system, I was ill prepared for the insularity of the Canadian entertainment industry. Never invited to audition for the prestigious Stratford or Shaw Festivals, or even any of the regional theatres in five years despite many applications, my work largely consisted of tiny parts in dreary TV crime re-creation dramas, where my artistic choices were restricted to wondering in which hand I should hold the flick knife. My income was sporadic but at least it provided me with a far more leisurely path to starvation than would otherwise have been available.

So Britain has always held a great attraction for me as the place that allowed me to train and develop whatever talent I may have, providing opportunities which my own country has not. I visit England as often as money permits (it goes without saying that I always have plenty of time), taking in as many plays as possible, seeing old friends and proposing madly to every British woman in sight.

Of course any female's understandably wary when she suspects the first thing to be fondled is her passport.

In any case I'd had enough of the twilight world of the illegal immigrant, and would never again attempt to stay anywhere without proper documentation.

And that was what I was attempting to tell an unsympathetic immigration officer who was refusing me entry, informing me that (despite my return ticket and protestations of honorable intentions to depart at the end of my vacation) he intended to send me back on the next available flight, preferably air freight. My passport was confiscated; I was escorted to the less welcoming part of the airport, politely ushered into a prison van, and driven to the Chateau d'If.

The Detention Centre, known as 'The Beehive’ for its shape, is the old control tower of Gatwick Airport, a relic of the days of Amelia Earhart, grass runways, and unrestricted access of Canadians to Britain. As a prison (and to me the distinction between prison and detention centre was less than academic) it comprises a large dayroom, male and female dormitories, and two unspeakable washrooms. My fellow inmates were a mixed bag of Chinese, Africans, Arabs, Latin Americans, Indians, and Turks, some traditionally dressed, all well behaved and fatalistic. None of them spoke English or the odd sort of French that one learns in Canadian high schools, so we communicated with smiles, gestures, and melancholy sighs, as one or more of my new friends were led out to their respective flights. The psychological torment began immediately when I noticed the only reading matter available was ancient issues of the Reader's Digest.

A further refinement of cruelty manifested itself at dinner. The British are an extremely fair people, and would never consider inflicting their own peculiar brand of cuisine on involuntary guests. So, several varieties of exotic comestibles, incandescently spiced, were set out for our delectation. My companions in misfortune dug in with relish, amused by my stricken expression and agonized expostulations. I looked as though I were gargling with napalm. Unfortunately, the concept of the middle-class Canadian as ethnic minority has made very little impact on international relations, and my own traditional dishes were not available. A toasted tuna sandwich proving too exotic for the caterers, I certainly wasn't going to try for a mooseburger.

Since my flight was scheduled for late the following day and the paper bedsheets provided not being particularly conducive to sleep, I sat up all night talking to my guard, who proved very sympathetic.

"Look, mate," he said, "you have the right of appeal up to the moment we put you on the plane. Talk to the Chief. There's still a chance. We do like Canadians, even if we have to be part of Europe now. No one really gives a damn how many of you come here. Two hundred thousand's no problem." He laughed. "Of course, 200,000 Iranian fanatics would be, an' if you don't believe me, ask Salman Rushdie. Mind you, we ain't allowed to say that. Isn't there anyone who could vouch for you, guarantee you'd leave on time? Someone English, respectable?"

And I suddenly realized there was. I had access to the ultimate weapon, and her name was Katherine.

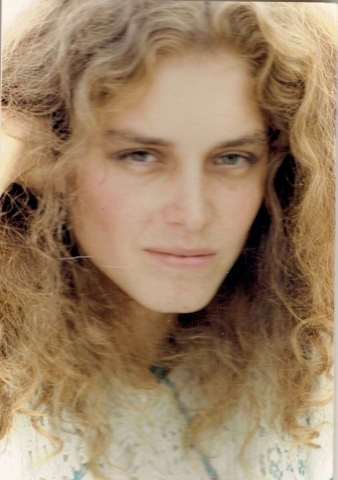

Katherine's beautiful. She has green eyes, an explosion of hair which tumbles in a golden brown cascade, and a face and figure so closely approximating the Romantic ideal as to make Helena Bonham Carter hang up her corset in abject defeat. In contrast, I have a shaved head, dark deep-set eyes, and jutting black brows, a combination that has blessed me with the sort of boy-next-door looks which are often found if one lives next door to a prison for the criminally insane. As a couple, we look like the preliminary to a purse-snatch.

It's one of those peculiar cases of opposites attracting. We'd been together now and again over the years, eventually forging something of an affectionate armed truce. In her case, at least, this manifests itself as very occasional exasperated adoration, more often tempered by feelings for me approximating those of Lucrezia Borgia towards her dinner guests.

But would she help? Well, I've grasped at flimsier straws. So I leapt for the payphone and started babbling.

"You actually expect me to visit you in a prison?" she asked rhetorically, her tone glacial.

"Well, I've brought you a pair of knee-high Red Indian moccasins, hand-beaded, with beaver fur shafts..."

"I'll be right over, you poor thing." Amateur students of female psychology, take note.

Reinforcements safely on the way, I somehow managed to secure an appointment to plead my case before an extremely unwilling Chief of the Immigration Section. With the situation at a critical point, my sense of the dramatic began to assert itself. I needed to be very impressive indeed, and the setting still wasn't quite right. "Have you a set of chains?" I asked the guard hopefully.

His expression suggested that he felt a straightjacket might be more appropriate. "Yeh, of course we do, but I'm not puttin' 'em on you just so's you can impress your girlfriend."

Damn, no props. Of necessity, this production was going to be minimalist. Undeterred, I assumed an expression and demeanor of nobility in extremis, eminently suitable for portraying Alfred Dreyfus on Devil's Island, and waited.

Before too long, several iron doors slammed and Katherine entered, dressed in twin set, pearls, and tweed skirt, looking as if she'd been manufactured by Laura Ashley and was available in finer shops everywhere. Several prisoners and the guard instinctively rose to their feet. I attempted a devil-may-care smile, which she countered with an expression like that of a mem-sahib who has strayed into the bazaar, giving the impression she'd soon be reaching into her reticule for the sal volatile.

"The van's here," said my guard. "It's time to go. And the very best of luck to you both."

Katherine touched my hand gently, a beautiful Chekhovian heroine coping with a lover's Siberian exile. The guard politely averted his gaze. Her eyes moist, her voice catching, she faltered, "Perhaps I can do nothing for you... They might take you away..."

"Yes," I murmured.

“So… could I have my moccasins now, please?”

A wardress directed me into the rear of the Black Maria, slammed the doors, and turned to Katherine. "You're not a prisoner, miss, so you're welcome to ride up front with me," she said, suppressing a curtsey and assisting her to the passenger seat.

"Never mind, my darling," I smiled, synthesizing a careless laugh that verged on the hysteric, "think of all the new experiences we're sharing!"

Katherine coloured slightly, bestowing a brief glance upon me through the iron mesh which sealed off the driver's compartment. If looks could dismember, I'd have attended my hearing in several baskets. The van moved off. Tired of playing Alfred Dreyfus, I decided to assume an agonized expression of martyred grandeur as I gave a superb performance of "Sydney Carton on His Way to the Guillotine."

Upon our arrival, we were ushered into the office of the Chief Immigration Officer, an august presence before whom Torquemada might have quailed. He sat at his desk, my voluminous dossier open at his elbow, regarding Katherine and me in baffled silence for a few minutes like someone watching a strange reinterpretation of The Tempest in which Miranda elopes with Caliban.

"You have five minutes, Mr. Hartman," he intoned, "then I'm going to refuse you."

I immediately began an impassioned 45- minute exhortation that drew equally on the schools of Lord Denning and Demosthenes. I could tell that the eccentricity of the situation had begun to appeal to him. After all, the average illegal immigrant's ambitions do not include claiming cultural refugee status and attempting to join the Royal Shakespeare Company.

But he preferred to have a strictly legal basis upon which to admit me, rather than by simply exercising official discretion.

"Let's see." he ruminated, "Hartman. What's your ancestry? Are you German?"

I knew exactly what he was driving at. As it happens my ancestry is Austrian, Grandfather having emigrated in the early 1890s, leaving behind a heartbroken Kaiser Franz Josef along with the second "n" in our surname, it having been washed overboard during a storm on the voyage and never seen again. But the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, two World Wars and shifting borders had placed the extremely battered remains of the ol’ family homestead smack in the middle of the Ukraine- not a member of the EU.

Germany, however, is, and I idly began to wish that my late father Joe had not been an undistinguished Canadian office worker but rather... SS Sturmbannfuhrer Josef von Hartmann, that monocled, black-uniformed, heel-clicking Prussian fiend now lounging in sombrero'ed ease on his Paraguayan hacienda, one of Hollywood's frothing Teutonic stereotypes whose sole wartime hobby consisted of shrieking passages from Mein Kampf while machine-gunning legions of British POWs.

That would have made me completely admissible. The immigration officer conceded that, as a private citizen at least, he found this unfair. I pressed my advantage.

“The whole thing makes no sense. Same language, same form of government, same ethics, same judicial system, same lady on the coins. My Uncle Harold even helped to liberate Holland. And what about all those hours I spent in Cub Scouts, learning about Baden-Powell, the Empire, and the Three Flags That Make Up a Union Jack? Can't I have the benefit of the doubt?"

The awful majesty of his judgment balanced on a razor's edge. He turned to Katherine as final arbiter. “All right. IF I admit him for three weeks, will you see that he leaves as he’s promised?"

She inclined her head regally.

"And if he doesn't?"

Katherine paused. And then she spoke, her jade-green eyes enormous, her accent so refined as to make a conversation in a Belgravia drawing room sound like a brawl in some waterfront gin mill.

"Thet", she pronounced, "would reflict tirriblay on my femly."

The officer nodded sagely, a Lord Chief Justice utterly convinced by a brilliant QC's unarguable legal submission, and immediately stamped my passport with a time-limited entry clearance.

My former guard carried my suitcase through customs for me, winked at Katherine and slapped me on the back. “Ain't never seen nuffink like that before”, he grinned. "Well, back to the dungeon," and left us.

We looked at one another, two successful campaigners, she shrieked happily, and in a rare display of affection, flung herself at me, one of those endless embraces that blots out the rest of the world. Life can really be grand on occasion. Not that particular occasion, though. When we came up for air, I noticed that some less romantically inclined individual had walked off with my suitcase.

Addendum

I received my UK citizenship in the late ‘90s, and have been with someone quite delightful now since 2005, happily married to her since 2006, and I fervently hope the two of us can go on for as long as possible together.

Katherine died by her own hand about five years before my wife and I met, she and I having parted at her request several years previously.

A fragment from Thomas Peacock (1785–1866) sums the two of us up all too well:

Whatever span the fates allow,

Ere I shall be as she is now,

Still in my bosom's inmost cell

Shall that deep-treasured memory dwell:

That, more than language can express,

Pure miracle of loveliness,

Whose voice so sweet, whose eyes so bright,

Were my soul's music, and its light,

In those blest days, when life was new,

And hope was false, but love was true.